Today I stumbled upon a tweet from Jeffrey Zeldman about Progressive Reduction. I was so intrigued by the sound of the term that I couldn’t resist digging a little deeper. Let’s see what this term is all about and discuss it’s pros and cons.

It all started when LayerVaults` Allan wrote a post explaining the concept of Progressive Reduction as follows:

Usability is a moving target. A user’s understanding of your application improves over time and your application’s interface should adapt to your user.

While I understand and agree with the basic idea, I’m not convinced that it’s flawless and feel we should perhaps be a little more skeptical about such approaches even if they sound incredibly nice (Read my recent post about design trends).

The concept is definitely effective in a perfect world where you have very accurate and up-to-date knowledge of your users’ ever changing proficiency. You can then intelligently adapt the UI allowing people to achieve their goals faster and more efficiently.

Unfortunately though… We don’t live in a perfect world.

The idea of Progressive Reduction holds the potential of bringing a whole new level of complexity to development and user testing. First, how will users react to those changes? If the change is too big, users might get confused. If the change is insignificant – why even bother? Or picture the situation when you want to teach a friend how to use an application, but it looks different on his device because he’s in another stage of progress, wouldn’t that feel strange?

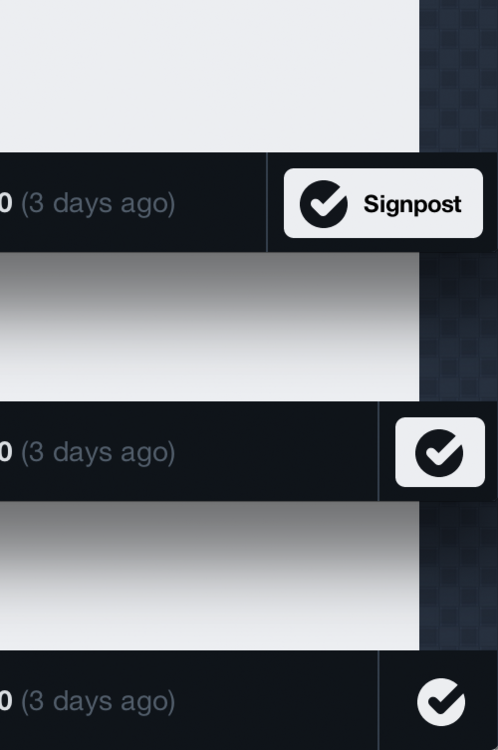

Let’s have a look what LayerVault did:

At first glance, their approach looks like a nice UX optimization. But, in practice, does it offer enough value that you should incorporate it in your project?

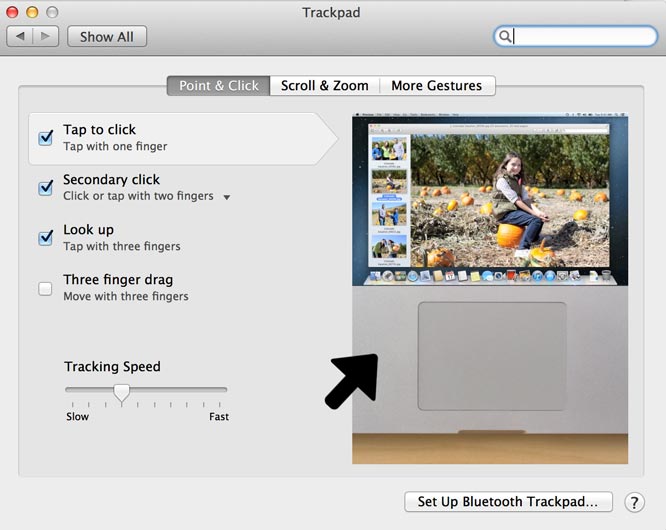

Progressive Disclosure VS Progressive Reduction

It was a few years ago that another “progressive” word made its appearance. That word was Progressive Disclosure. The idea of the latter is to minimize an interface to it’s core parts and then reveal further relevant content as soon as the user requests it.

As you can see the concept works out perfectly because it can dramatically reduce UI clutter without any significant drawback. I’m not so sure about Progressive Reduction though.

Jef Raskin, best known for his work at the Macintosh Project at Apple, describes the problems of invisible UI elements in his Book “The Humane Interface”. He claims that the user should always be in control of an application. When a user interface suddenly changes, will this still be the case? Can he undo it? Will there be a control panel for it which eventually increases the complexity of the application after all? What happens if the user doesn’t use the application for a while? At which time exactly will you show the reduced version? Questions upon questions…

The Fact: We are creatures of habit

It’s not a secret that we are creatures of habit. Habits build the foundation of user experience; they define the way we use applications and increase efficiency. Raskin even argues that we should deliberately take advantage of the human trait of habit development and further argues:

An interface is humane if it is responsive to human needs and considerate of human frailties.

An interface should be responsive to human needs. Is Progressive Reduction a move towards more responsive interfaces? Possibly. Simon Raess, founder of Ginetta Web / Design and former Product Designer at Google pointed me towards two interesting phenomena we can bring in to assess this concept from a more scientific and psychological point of view. These concepts go with the name Change Blindness and Change Aversion.

Change Blindness & Change Aversion

Change Blindness can be described as a psychological phenomenon that occurs when a change in a visual stimulus goes unnoticed by the observer (wikipedia). In theory that would mean that an unsubstantial change on an interface will not be consciously noticed by most users. The longer people use an application the more patterns evolve which end up in muscle memory and automatic reflexes. Could this be an indication that Progressive Reduction could work after all? Time will tell.

While the theory of Change Blindness relates to users who do not take notice of changes, Change Aversion could be considered as pretty much the opposite. Aaron Sedley, UX Researcher at Google defines it as follows :

Change Aversion is the negative short-term reaction to changes in a product or service. It’s entirely natural, but it can be avoided — or at least mitigated.

In his blog he shares some ideas on reducing Change Aversion and emphasizes that Change Aversion can in fact be mitigated. Among others you should clearly communicate the nature and value of the changes as well as offer the possibility of going back. To enable all this, you still need to embed this functionality somewhere, and that’s the actual problem.

Conclusion

While some of the disadvantages mentioned can be solved by paying close attention to the concept of Change Aversion, there are still a lot of questions that remain to be answered. Does the advantage of a less cluttered UI justify the sudden change of it with all the possible risks involved? Eventually only user testing will help us to better understand the impact on the final user experience. One thing is for sure though, if such UX concepts are not used by paying close attention to details it can quickly do more harm than good.

I believe that we should aim at building applications & websites that focus on the essence from the very beginning which should make such concepts obsolete. There is a famous saying from a guy who might not have been a user experience designer but who sure knew what he was talking about:

Keep things as simple as possible. But not simpler.

Funnily enough, that guy was Albert Einstein.

So what’s your take on this? Do you have a project where you make use of this in the near future? Let me know on Twitter!